To powinien być coś jakby właściwy tytuł…

Pra-Słowiańskie Ssać / SSaC’, Sączyć / Sa”C”+yC’, Siąkać / Sia”K+aC‚, Sikać / SiK+aC’, Sok / SoK, Syk / SyK, itp, jako dowody na wtórne ubezdźwięcznienie / kentumizację pierwotnych postaci tzw. satem, na podstawie porównania pierwotnych odtfoszonych postaci tzw. PIE i tzw. atestowanych (zapisanych) słów, jak sanskryckie siñcáti, awestyjskie hiṇcaiti, starogreckie hîxai, czeskie scát, štím, chcát, itp.

siusiu (1.1)

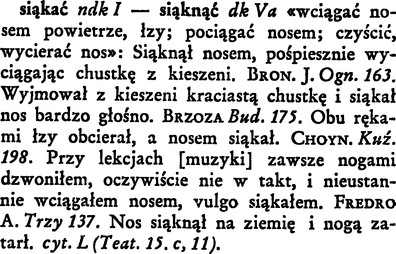

siąkać Słownik języka polskiego pod red. W. Doroszewskiego

UWAGA!

A oto Pra-Słowiańskie słowa, jak Sączyć / Sa”C”+yC’, Siąkać / Sia”K+aC’, Sikać / SiK+aC’, itd, które są źródłosłowami dla łacińskich słów z poprzedniej części. I znów pytanie za 1000 punktów…

Dlaczego Siąkać / Sia”K+aC’ i Sikać / SiK+aC’ nie „spalatelizowało” się w średniowieczu do *Siącać / Sia”C+aC’, *Sicać / SiC+aC’, hm?

To nie wszystko…

Przypominam, że w j. zachodnio-słowiańskim / lechickim / polskim dziwnie jakoś tak zachowały się postacie słów z występującymi w nich dźwiękami zapisywanymi znakami Z = G = H = K = S = C = T = D…

Zgodnie z ofitzjalnymi fyfodami nie powinno to jednak mieć miejsca, patrz tzw. średniowieczne palatalizacje słowiańskie, itp.

Przypominam, że wg Sławomira Ambroziaka, ofitzjalnych jęsykosnaftzów i wszelkiej maści allo-allo przeciw-logicznych i przeciw-słowiańskich wyznawców tradycji pustynnej, która swoje nazistowskie poglądy co do Słowiańszczyzny opiera jedynie na NIEPRAWDZIWYCH I CAŁKOWICIE ZMYŚLONYCH PODSTAWACH,.. było jakoś tak:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Proto-Slavic#Progressive_palatalization

(…)

Other vowel and consonant diacritics

Other marks used within Balto-Slavic and Slavic linguistics are:

- The haček on consonants (č š ž), indicating a „hushing” quality [tʃ ʃ ʒ], as in English kitchen, mission, vision.

- Various strongly palatal(ized) consonants (a more „hissing” quality in case of sibilants) usually indicated by an acute accent (ć ǵ ḱ ĺ ń ŕ ś ź) or a haček (ď ľ ň ř ť).

- The ogonek (ą ę ǫ), indicating vowel nasalization (in modern standard Lithuanian this is historical only).

(…)

Split from Indo-European

Proto-Balto-Slavic has the satem sound changes wherein Proto-Indo-European (PIE) palatovelar consonants became affricate or fricative consonants pronounced closer to the front of the mouth, conventionally indicated as *ś and *ź. These became simple dental fricatives *s and *z in Proto-Slavic:

-

*ḱ → *ś → *s

-

*ǵ → *ź → *z

-

*ǵʰ → *ź → *z

This sound change was incomplete, in that all Baltic and Slavic languages have instances where PIE palatovelars appear as *k and *g, often in doublets (i.e. etymologically related words, where one has a sound descended from *k or *g and the other has a sound descended from *ś or *ź).

Other satem sound changes are delabialization of labiovelar consonants before rounded vowels[32] and the ruki sound law, which shifted *s to *š after *r, *u, *k or *i. In Proto-Slavic, this sound was shifted backwards to become *x, although it was often shifted forward again by one of the three sound laws causing palatalization of velars.[33]

In the Balto-Slavic period, final *t and *d were lost.[34]

Also present in Balto-Slavic were the diphthongs *ei and *ai as well as liquid diphthongs *ul, *il, *ur, *ir, the latter set deriving from syllabic liquids;[35] the vocalic element merged with *u after labiovelar stops and with *i everywhere else, and the remaining labiovelars subsequently lost their labialization.[36]

Around this time, the PIE aspirated consonants merged with voiced ones:[37]

-

*bʰ → *b

-

*dʰ → *d

-

*gʰ → *g

Once it split off, the Proto-Slavic period probably encompassed a period of stability lasting 2,000 years with only several centuries of rapid change before and during the breakup of Slavic linguistic unity that came about due to Slavic migrations in the early sixth century.[38][39]

As such, the chronology of changes including the three palatalizations and ending with the change of *ě to *a in certain contexts defines the Common Slavic period.

Long *ē and *ō raised to *ī and *ū before a final sonorant, and sonorants following a long vowel were deleted.[40] Proto-Slavic shared the common Balto-Slavic merging of *o with *a. However, while long *ō and *ā remained distinct in Baltic, they merged in Slavic, so that early Slavic did not possess the sounds *o or *ō.[41][42][clarification needed]

(…)

First regressive palatalization

As an extension of the system of syllable synharmony, velar consonants were palatalized to postalveolar consonants before front vowels (*i, *ī, *e, *ē) and before *j:[49][50]

-

*k → *č [tʃ]

-

*g → *dž [dʒ] → *ž [ʒ]

-

*x → *š [ʃ]

-

*sk → *šč [ʃtʃ]

-

*zg → *ždž [ʒdʒ]

This was the first regressive palatalization. Although *g palatalized to an affricate, this soon lenited to a fricative (but *ždž was retained).[51] Some Germanic loanwords were borrowed early enough to be affected by the first palatalization. One example is *šelmŭ, from earlier *xelmŭ, from Germanic *helmaz.

(…)

Second regressive palatalization

Proto-Slavic had acquired front vowels, ē (possibly an open front vowel [æː][57]) and sometimes ī, from the earlier change of *ai to *ē/ī. This resulted in new sequences of velars followed by front vowels, where they did not occur before. Additionally, some new loanwords also had such sequences.

However, Proto-Slavic was still operating under the system of syllabic synharmony. Therefore, the language underwent the second regressive palatalization, in which velar consonants preceding the new (secondary) phonemes *ē and *ī, as well as *i and *e in new loanwords, were palatalized.[49][50][58] As with the progressive palatalization, these became palatovelar. Soon after, palatovelar consonants from both the progressive palatalization and the second regressive palatalization became sibilants:

-

ḱ → *c ([ts])

-

ǵ → *dz → *z

-

x́ → *ś → *s/*š

In noun declension, the second regressive palatalization originally figured in two important Slavic stem types: o-stems (masculine and neuter consonant-stems) and a-stems (feminine and masculine vowel-stems). This rule operated in the o-stem masculine paradigm in three places: before nominative plural and both singular and plural locative affixes.[59]

|

‚wolf’ |

‚horn’ |

‚spirit’ |

| Nominative |

singular |

*vьlkъ |

*rogъ |

*duxъ |

| plural |

*vьlci |

*rozi |

*duśi |

| Locative |

singular |

*vьlcě |

*rozě |

*duśě |

| plural |

*vьlcěxъ |

*rozěxъ |

*duśěxъ |

Progressive palatalization

An additional palatalization of velar consonants occurred in Common Slavic times, formerly known as the third palatalization but now more commonly termed the progressive palatalization due to uncertainty over when exactly it occurred. Unlike the other two, it was triggered by a preceding vowel, in particular a preceding *i or *ī, with or without an intervening *n.[29] Furthermore, it was probably disallowed before consonants and the high back vowels *y, *ъ.[60] The outcomes are exactly the same as for the second regressive palatalization, i.e. alveolar rather than palatoalveolar affricates, including the East/West split in the outcome of palatalized *x:

-

k → *c ([ts])

-

g → *dz (→ *z in most dialects)

-

x → *ś → *s/*š

Examples:

- *atiku(s) „father” (nom. sg.) → *aticu(s) → (with vowel fronting) Late Common Slavic *otьcь

- Proto-Germanic *kuningaz „king” → Early Common Slavic *kuningu(s) → Late Common Slavic *kъnędzь

- *vixu(s) „all” → *vьśь → *vьšь (West), *vьsь (East and South)

There is significant debate over when this palatalization took place and the exact contexts in which the change was phonologically regular.[61] The traditional view is that this palatalization took place just after the second regressive palatalization (hence its traditional designation as the „third palatalization”), or alternatively that the two occurred essentially simultaneously. This is based on the similarity of the development to the second regressive palatalization and examples like *atike „father” (voc. sg.) → *otьče (not *otьce) that appear to show that the first regressive palatalization preceded the progressive palatalization.[62]

A dissenting view places the progressive palatalization before one or both regressive palatalizations. This dates back to Pedersen (1905) and was continued more recently by Channon (1972) and Lunt (1981). Lunt’s chronology places the progressive palatalization first of the three, in the process explaining both the occurrence of *otĭče and the identity of the outcomes of the progressive and second regressive palatalizations:[63]

-

Progressive palatalization: *k > *ḱ (presumably a palatal stop) after *i(n) and *j

-

First regressive palatalization: *k/*ḱ > *č before front vowels

-

Fronting of back vowels after palatal consonants

-

Monophthongization of diphthongs

-

Second regressive palatalization: *k/*ḱ > *c before front vowels

(similarly for *g and possibly *x)

Significant complications to all theories are posed by the Old Novgorod dialect, known particularly since the 1950s, which has no application of the second regressive palatalization and only partial application of the progressive palatalization (to *k and sometimes *g, but not to *x).

More recent scholars have continued to argue in favor of the traditional chronology,[64][65][66] and there is clearly still no consensus.

The three palatalizations must have taken place between the 2nd and 9th century. The earlier date is the earliest likely date for Slavic contact with Germanic tribes (such as the migrating Goths), because loanwords from Germanic (such as *kъnędzь „king” mentioned above) are affected by all three palatalizations.[67]On the other hand, loan words in the early historic period (c. 9th century) are generally not affected by the palatalizations. For example, the name of the Varangians, from Old Norse Væringi, appears in Old East Slavic as варѧгъ varęgъ, with no evidence of the progressive palatalization (had it followed the full development as „king” did, the result would have been **varędzь instead). The progressive palatalization also affected vowel fronting; it created palatal consonants before back vowels, which were then fronted. This does not necessarily guarantee a certain ordering of the changes, however, as explained above in the vowel fronting section.

(…)

…..

I co? I pstro, bo to wszystko powyżej to jedynie jedna wielka odtfoszona gówno prawda. Tak samo wiarygodna, jak rzekome zapożyczenie słowa Pra-Słowiańskiego Cyce / CyCe, od jakiegoś giermańskiego Zitze / ZiT+Ze, czy Titte / TiT+Te…

Zwracam uwagę, że znów tzw. rough breathing, czyli wtórne ubezdźwięcznienie jest doskonale widoczne i działające, patrz przykłady podane niżej.

I znów zapis zgodny z zasadą tzw. miękkiego k’/K’, w skrajnej postaci, patrz Sławomir Ambroziak i Pra-Słowiańskie rdzenie naprzemiennie, raz tylko wysokoenergetyczne tzw. satem, dwa wysokoenergetyczne, ale już jakoś częściowo wtórnie ubezdźwięcznione, czyli zkentumizowane. Co ciekawe, postaci tylko ubezdźwięcznionych jakoś nie znalazłem, no bo Pipi / Pi+Pi, Wee-wee / L”i+L”i, itp no to chyba nie to samo…

…..

http://www.forumbiodiversity.com/showthread.php?t=50229

Kentumizacja – wtórne ubezdźwięcznienie wysokoenergetycznych pierwowzorów PS, na przykładach Sikać, Szczać, itp.

Czytaj dalej →